And now for a tiny piece of wisdom from our friend Catherine Arcolio at Leaf and Twig:

what separates us will shatter or melt if we stay with love

Source: Eventually

And now for a tiny piece of wisdom from our friend Catherine Arcolio at Leaf and Twig:

what separates us will shatter or melt if we stay with love

Source: Eventually

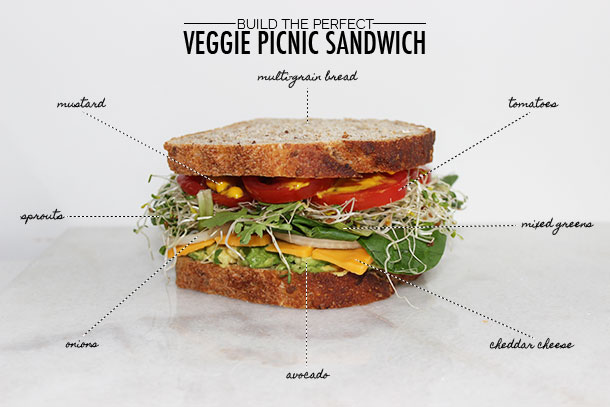

Since the dawn of lunch, roughly the mid-eighteenth century, when John Montagu, the Fourth Earl of Sandwich, too busy gambling with his friends to eat a real meal, asked his valet to bring him some meat in between two slices of bread, people have appreciated the portability of the sandwich.

The two places where I work are both nearby a Rebecca’s and an Au Bon Pain, so you can imagine that I have been eating a lot of sandwiches recently, some of them remarkably better than others. And just when I finally find a sandwich I can fall in love with, the place changes the menu, and not for the better. And even when you get the same sandwich on Friday, for example, that you also got on the previous Tuesday, the person who makes it can make all the difference. (Note to Au Bon Pain: mustard is a condiment, not a soup. The same goes for lemon aioli.)

Disappointments abound, but humans are aspirational creatures. If we weren’t, the species would have pretty much petered out by now, given how often love fails. And we can’t even blame Disney for our apparent optimism. When was the last time you heard a bunch of forest animals singing about the happy ending that was surely in the human characters’ future: to wit, a perfect sandwich? (Okay, the closest thing I can think of to this would be the animated film, Over the Hedge, where the animals go through the humans’ trash like connoisseurs.)

And I just discovered that “Club Sandwich” means that there is an extra piece of bread in the middle, a hundred needless calories where there could be Meaningful Filling of Actual Substance. Harrumph.

One of my favorite poems that I didn’t write is “The Art of Blessing the Day” by Marge Piercy. It is framed in a way that uses some of the language of religion to talk about the beauty of the thing-ness of our lives and the events that don’t automatically get celebrated formally. It is in fact about poetry itself, in the widest sense, which is the sense I much prefer to the very narrow sense we get taught in school.

The Art of Blessing the Day

This is the blessing for rain after drought:

Come down, wash the air so it shimmers,

a perfumed shawl of lavender chiffon.

Let the parched leaves suckle and swell.

Enter my skin, wash me for the little

chrysalis of sleep rocked in your plashing.

In the morning the world is peeled to shining.

This is the blessing for sun after long rain:

Now everything shakes itself free and rises.

The trees are bright as pushcart ices.

Every last lily opens its satin thighs.

The bees dance and roll in pollen

and the cardinal at the top of the pine

sings at full throttle, fountaining.

This is the blessing for a ripe peach:

This is luck made round. Frost can nip

the blossom, kill the bee. It can drop,

a hard green useless nut. Brown fungus,

the burrowing worm that coils in rot can

blemish it and wind crush it on the ground.

Yet this peach fills my mouth with juicy sun.

This is the blessing for the first garden tomato:

Those green boxes of tasteless acid the store

sells in January, those red things with the savor

of wet chalk, they mock your fragrant name.

How fat and sweet you are weighing down my palm,

warm as the flank of a cow in the sun.

You are the savor of summer in a thin red skin.

This is the blessing for a political victory:

Although I shall not forget that things

work in increments and epicycles and sometime

leaps that half the time fall back down,

let’s not relinquish dancing while the music

fits into our hips and bounces our heels.

We must never forget, pleasure is real as pain.

The blessing for the return of a favorite cat,

the blessing for love returned, for friends’

return, for money received unexpected,

the blessing for the rising of the bread,

the sun, the oppressed. I am not sentimental

about old men mumbling the Hebrew by rote

with no more feeling than one says gesundheit.

But the discipline of blessings is to taste

each moment, the bitter, the sour, the sweet

and the salty, and be glad for what does not

hurt. The art is in compressing attention

to each little and big blossom of the tree

of life, to let the tongue sing each fruit,

its savor, its aroma and its use.

Attention is love, what we must give

children, mothers, fathers, pets,

our friends, the news, the woes of others.

What we want to change we curse and then

pick up a tool. Bless whatever you can

with eyes and hands and tongue. If you

can’t bless it, get ready to make it new.

***

I think Piercy gets to the heart of the matter when she says:

The art is in compressing attention

to each little and big blossom of the tree

of life, to let the tongue sing each fruit,

its savor, its aroma and its use.

The work of the poet (not unlike one of the tasks of the lover) is to pay attention to the details. God is in the details. We have only to look, and we have to look. We look at everything outside ourselves, and then, if we dare, we can start to look at all the things that are inside ourselves, and then we look out again.

And then we write.

Marge Piercy. The Art of Blessing the Day. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1999.

Concrete poetry is the practice of making a poem look, on the page, like its topic. In the days of the typewriter, this took a lot of time, but when published, it has great appeal. On the interwebs, where everything has to be left justified, concrete poetry is pretty much just a silhouette. But there are ways to get around that, if all you are going for is the idea of the topic rather than an actual illustration. Here is one from a group of poems I am trying to put together about the dailiness of my life.

7:40 a.m.

BASE BASE

color color

liner liner

lashes lashes

BOTH

LIPS

coffee coffee coffee

coffee

coffee

I am reposting this scintillating sonnet by Robert Okaji because it is genius.

If You Were a Guitar If you were a guitar I would play you till my fingers grew rough from your body’s touch, till the moisture in the clouds withdrew and only music rained on. But what breeze coul…

Source: If You Were a Guitar

Unless you are e. e. cummings, the odds are quite good that you usually use capital letters for many things in your writing, but my question is how do you feel about the first letter of each line in a poem? Dropping the first letter to lowercase makes it feel to me as if you are simply talking as you would in a paragraph, and especially if you are rhyming (which as you know I normally avoid like the plague) hopefully keeps your readers from reading each line on its own, as if it had no grammatical connection the line that came before or the one after.

That is all well and good, but has anybody explained this to Microsoft Word? If you don’t want every line after a return to start with a capital, you have to go into some toolbar menu and unclick the default. And of course, with each new (usually worse, less convenient) version of Word, the Byzantine lengths to which you must go to achieve this get more annoying. For this reason, among others, I have been being lazy, and capitalizing.

Thoughts?

So yesterday as I was riding the train to work, the loudspeaker announced, “Destination: North Station.” But what I heard was “Fascination: North Station.” And I thought, “Yep, it’s true what they say. It’s not the journey; it’s the fascination.”

Simply fascination: the purr of the train as it glides

East, seaward, never to reach the ocean as it might

Desire to: our needs command the journey to end

Far short of the ebb and flow of tides. Our work

Calls us into the city that squats delicately on

The edge of the Charles River, but only that

River has the privilege of reaching the sea,

Joining its flow with the far greater fascination

Of the blue-green rolling, rolling, West, then

East, as we will eight hours from now, and home.

Scheherazade Speaks

For nearly thirty-three months, I told an unfinished tale

To the king who had promised to kill his wife each night

So that she could never be unfaithful, then marry again

The next night. I who had spent my youth in the library

Of my father’s home, knew many tales, a thousand

And one in all. I secretly vowed to bend him to my will.

Painting by Ferdinand Keller, 1880.

“Man, sometimes it takes you a long time to sound like yourself.” –Miles Davis

So I was thinking about this line from Miles Davis (because it turns out that epigraphs are a great way to overcome your writer’s block), and I thought about how we constitute the self. And then I had that last stanza from Philip Larkin’s poem “This Be the Verse” go through my head, one of the very few pieces of poetry I have memorized:

This Be The Verse

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

But they were fucked up in their turn

By fools in old-style hats and coats,

Who half the time were soppy-stern

And half at one another’s throats.

Man hands on misery to man.

It deepens like a coastal shelf.

Get out as early as you can,

And don’t have any kids yourself.

Now, I will admit that this is more than a bit cynical and that I have been relatively lucky in my upbringing, but there is also some good sense to it, as when people have pain, they tend to spread it around like manure, but generally without the benefit of nourishing anything. Still the eight-syllable line and abab rhyme scheme together make for a catchy (and therefore more memorizable) poem, even if does get a little sing-songy, which maybe takes away from the seriousness. So I adopted some of this to create my own bit.

The Tri-fold Self

Three things make up the self, I think:

The mind, the body and the voice.

Such things are passed on down to us

Without our say-so or our choice.

First comes the mind, the wandering wit

That tilts at windmills, fights through mazes,

Eats the words served up in books

And dreams the world in smoky hazes.

Next comes the body, old workhorse

That carries Mind from place to place.

We exercise to keep it fit

And use makeup to gild its face.

Last comes the voice, through which the mind

Speaks from this body to that.

And other minds judge what they hear

And call us either sharp or flat.

It takes long practice to learn how

The mind best works itself to learn,

Itself a cosmos hidden deep

Within the body, there to burn.

And longer still it takes to see

The beauty in the body aging,

Aching, creaking, fighting, winning,

Singing, all while life engaging.

But longest yet it takes the ears

To love the sound the tongue releases

From the moment we, born, wail

Until our last, when all breath ceases.

And so it is, all of us struggle

To be ourselves: voice, body, mind.

You know the struggle all too well,

So as you walk the world, be kind.

Reposted from The Guardian 26 Feb. 2016:

“The Black Mambas are winning the war on poaching,” insists Siphiwe Sithole. “We have absolutely zero tolerance for rhino poaching and the illegal wildlife trade. The poachers will fall – but it will not be with guns and bullets.”

Sithole and Felicia Mogakane are members of South Africa’s Black Mambas, the world’s first all-female anti-poaching unit that has captured the public’s imagination. But it’s their success in reducing rhino deaths and breaking down the barriers between poor communities and elite wildlife reserves that is their most powerful weapon in the war on poaching, and has seen them pick up their second international conservation award this week.

The two women have travelled to London to receive the inaugural Innovation in Conservation award from UK charity Helping Rhinos. The award recognises projects “with an inspiring and innovative approach” that have shown positive results in protecting rhino populations.

Since forming in 2013, the Black Mambas have seen a 76% reduction in snaring and poaching incidents within their area of operation in Balule nature reserve in the country’s north-east. As well as the famous big five of rhino, lion, elephant, buffalo and leopard, the 40,000-hectare private reserve is home to zebra, antelope, wildebeest, cheetah, giraffe, hippos, crocodiles and hundreds of species of trees and birds.

In the six months before the Mambas were set up, 16 rhinos were lost in Balule, one of several private reserves bordering Kruger national park. In the 12 months after, fatalities were reduced to just three rhinos.